First of all, what is a charrette?

In literal terms, it’s the French word for cart. Architecture studios employ drafts-people who toil away at technical drawings against deadlines. In the old days when drawing deadlines approached, before computers and digital platforms, a collection cart would come down the office aisle and if a drafter wasn’t able to get their drawings on the cart before it went by, they’d risk getting a pink slip. So, the approach of the cart, or charrette if you’re in France or Belgium or parts of Alsace, could cause great stress. It’s all about finishing on time. In this sense, the word charrette has come to mean working on your design drawings as fast as you can to meet a deadline.

Picking up on the importance of the term, two Harvard Graduate School of Design students, Lionel Spiro and Blair Brown, established a technical drawing supply store in Cambridge, MA in 1964. They adopted Charrette as the business name. It’s where we found all our triangles, templates, compasses, trace paper, inks and charcoal. They even had a small outlet in a small concrete closet of Harvard’s design school at Gund Hall. We’d run downstairs for emergency sheets of chipboard, a roll of trace, or lichen for our site models.

Today’s Charrette

The idea of charrette has evolved to signify a self-imposed short-term, high-pressure, high-output event where professional designers and other contributors focus to generate solutions for a particular set of problems over a given period. Typically, the effort ends with somewhat polished graphics, charts, drawings, and text to convey the complexities of the work. Organizations typically put on the events, and they last for one to three days. There is even a charrette association that recommends best-practices.

The original sense of a charrette remains in colleges and graduate schools and offices whenever a tight deadline approaches. Cramming until dawn can be the norm, but in the past few decades, student associations have demanded better treatment than that which requires overnight work. In the end, those demands matter little; the work will be done. However, it is acceptable only when self-imposed.

Long after I was out of school, I took part in charrettes as a member of the Urban Land Institute (ULI) in organized efforts to help municipalities that had applied to the ULI for help with particular problems. ULI charged only a nominal fee and brought together volunteers from landscape architecture, building architecture, real estate law, finance, and banking, town planners and urban designers, traffic engineers, civil engineers, art advocates, and others as needed. The last ULI charrette I was on focused on the prospect of a multi-modal transportation center in Fitchburg, MA. Planners anticipated that facility would serve MBTA commuter rail, regional bus lines, and taxis. Ride-sharing was not yet a thing on the East Coast. Today, the Fitchburg Transportation Center functions well.

More recently, I take part in charrettes with an organization I joined several years ago and am happy to support: Plan NH is a non-profit group of volunteers actively working in the professions of development, design, building, and management of our built environment. Plan NH has conducted a couple of charrettes per year since 1986, completing over eighty to date. So far, I have helped on five charrettes with Plan NH, in Brentwood, Manchester, Campton, Newmarket, and Nashua. Below is a clip from the Union Leader newspaper covering the Nashua event.

Plan NH

Each of Plan NH’s charrettes takes place over a Friday from about 9:00 AM through 5:00 PM the next Saturday. Cities and towns apply to Plan NH detailing the issues they would like to solve. They include information on what they have done to date to achieve their ends, and how coordinated their community is in the effort. For instance, are the fire and police and administrative departments unified in their commitment to helping to realize the proposed changes or improvements? How clear are the goals? Is the general citizenry behind the effort? Are the goals appropriate for the issues that Plan NH is comfortable tackling?

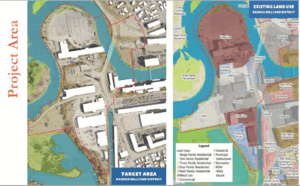

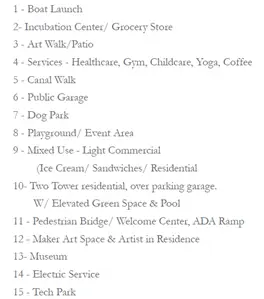

The City of Nashua recently applied for help to revitalize its Mill Yard district. It’s full of a few run-down buildings deserving of the wrecking ball, and a few that are in fine shape and still operational. So, the surgical removal of the unsalvageable structures, upgrades to the good ones, and installation of new buildings became an aim. Better circulation became another goal to improve walkers’, riders’, paddlers’, and drivers’ experiences. Better recreational amenities and access to the river were called for to help improve one abutting neighborhood that stands as New Hampshire’s lowest income community, and the better off districts adjoining the Mill Yard.

The Process

Our first step was a tour of the Mill Yard and surrounding districts, guided by Nashua’s Planning Department staff. These people know the city as well as anyone. There are typically twelve to fifteen volunteers on our team, sometimes twenty. City employees gave us insights into problem traffic areas, hidden cultural outlets, unused parks, under-used riverfront, new construction of commercial space and housing and municipal infrastructure, the better eating spots, where kids hang out to do their thing, and so forth.

With that background, we regrouped at City Hall, and over lunch we met with Nashua’s main stakeholders: the Chief of Police, the Mayor’s office, the Planning Department, the DPW, and business owners with a vested interest in the city. We heard their impressions of the Mill Yard’s problems and opportunities, and what they would like to see change and improve there.

Meeting with town officials and business owners in Campton, NH

Well-armed with loads of information, we readied for our first of two meetings with the public. We orchestrate our interaction with the public because there is always at least one person who needs to dominate the setting, get their voice heard, raise random objections, criticize the process as unfair, and inform us that our work is in vain. Sometimes there are two folks like that. So, we divide into groups so we can conquer the naysayers and get some real feedback from the community. In each group we have a facilitator (that’s the part I like) and a recorder. The facilitator reviews the process, manages the discussion, and keeps things rolling to a tight schedule. We ask three questions, and among the five or six townspeople at each table, we allow ten minutes per question to get everyone’s feedback and memorialize it on big blotter pads.

Our three questions are always the same: What do you see when you think about or walk through or drive by the subject property? What would you like to see there? What more should we know about it? We select one citizen at each table to present the top three most important points as decided at the table. A grand note-taker at the head of the room records all the points given.

That takes about ninety minutes. Then we break for a quick dinner provided by the town, usually catered gratis by a local restaurant. After dinner, we do it again with a new batch of townsfolk.

One Day to Produce

This is when the real work starts. After the townspeople leave and we volunteers are cloistered to strategize, we figure how to make the most of the information we’ve collected. Some of us will go out to the subject property to confirm conditions or fill in missing data. Some will review the notes collected at the three meetings. Others will start collecting photos we’ve taken on the tour and upload them to a cloud database set up for this charrette. Meanwhile, we transform the enormous conference room from a series of information-gathering tables to a production setting for research, planning, design, drawing, engineering, and collaborating on best-case scenarios for the subject property.

Finally, about 9:00 PM that Friday, we’ll peel off to our hotel or drive home. Usually several of us will debrief at a bar that might also serve food. There we get to cut loose with some of our impressions of the day. There are inevitably a few people at this debriefing whom we haven’t met before the charrette, a town administrator or town planner, so it’s always interesting.

By 8:00 Saturday morning, the team of volunteers had gathered again at City Hall to formulate quick solutions. The ideas reflect our insights that percolated throughout the prior day and evening. The city provides large-format (36” x 42” and 24” x 36”) color plans of the area at two or three different scales. These allow us to give several general overview renditions of property-wide themes and solutions, at a macro scale, and more detailed close-up views of all the areas under our consideration.

We start with a group meeting for about an hour and a half to hash out alternatives and realistic options. Designers ensure all solutions are physically feasible to be built. We leave politics aside, as that is a rabbit hole we don’t have time to explore. Usually, a few people have really thought hard about improvements, and most others add good ideas through the day.

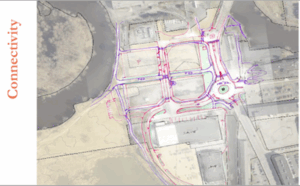

The traffic engineers start figuring changes in street directions, locations for a new roundabout, new parking alignments on streets, expanded sidewalks and neck-downs and raised crosswalks and so forth.

A conceptual sketch of potential roadway adjustments to benefit the neighborhood

Others pick an area and work in small groups to explore better circulation, building massing, use of open space and amenities, revisions to the zoning code, sight lines, civic monuments, and all the things that go into improving a community.

Team members reviewing drawings and approach

Wrapping Up

After about four hours of cranking out ideas and sketches, we finalize our drawings in collaboration among all the teams. We set our presentation for 3:00, meaning the charrette will roll by at around 2:30. The group spends those last minutes polishing the drawings and photographing them to upload to a PowerPoint slide deck. Usually, the drawings are all done by hand and augmented with notes via graphics programs.

Around 2:45, the public starts arriving for the final presentation, getting settled and watching the frantic buzzing as we wrap up. The presentation takes about an hour. There are introductions and explanations of the process the city has undertaken for this charrette. There is a description of the application process, who directed it, and how Plan NH helps communities. As teams, we present our ideas and drawings that we’ve created. Sometimes a townsperson gets bent out of shape because we’ve suggested a change that might not benefit them personally, or their property might need to adjust to accommodate an enormous improvement. Our recommendations are generally well received, and the enthusiasm in the room is palpable.

Over the next several weeks, team members edit and compile the information and notes and data into a final report. During that time, the compilers ask each of us volunteers to review a report draft for accuracy and completeness. Finally, Plan NH delivers the finished report to the town. What they do with our recommendations is entirely up to them.

A few years after a charrette, Plan NH might conduct walking tours for its members to review the progress that certain towns have made. Observing real change is a slow process, but our work is gratifying. We have a great sense of accomplishment at the end of each charrette, knowing that folks at the top of their field can come together on a volunteer basis to help small and large communities realize their dreams for a better community.